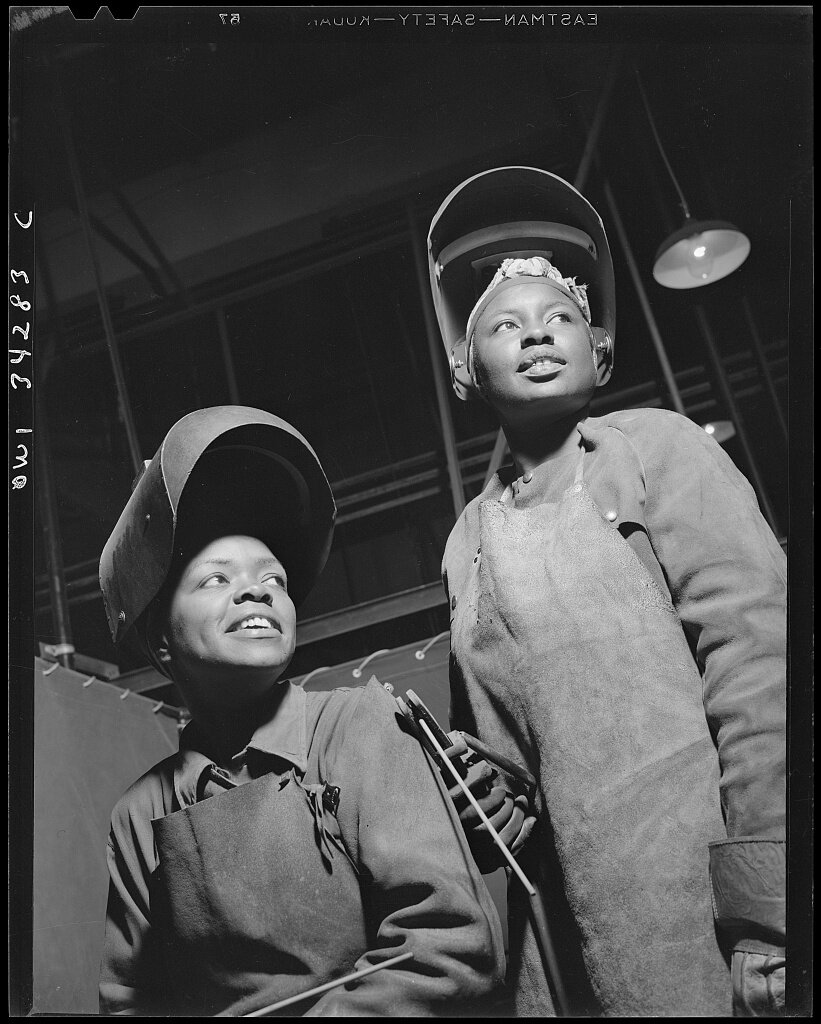

New Britain’s Women in War: Real Life Rosies

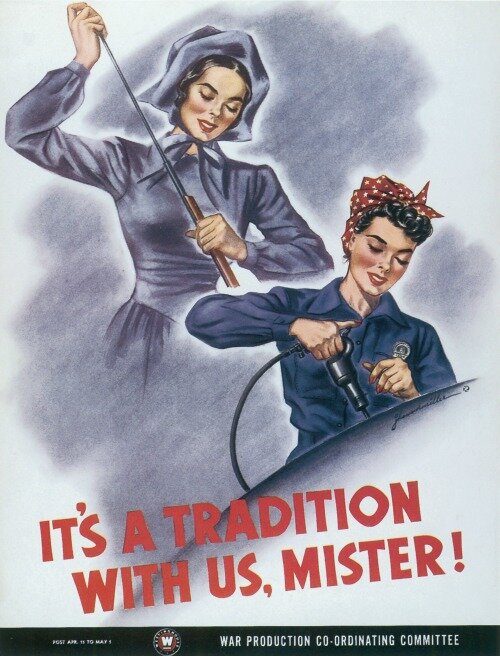

“We Can Do It!”

Howard J. Miller, 1943.

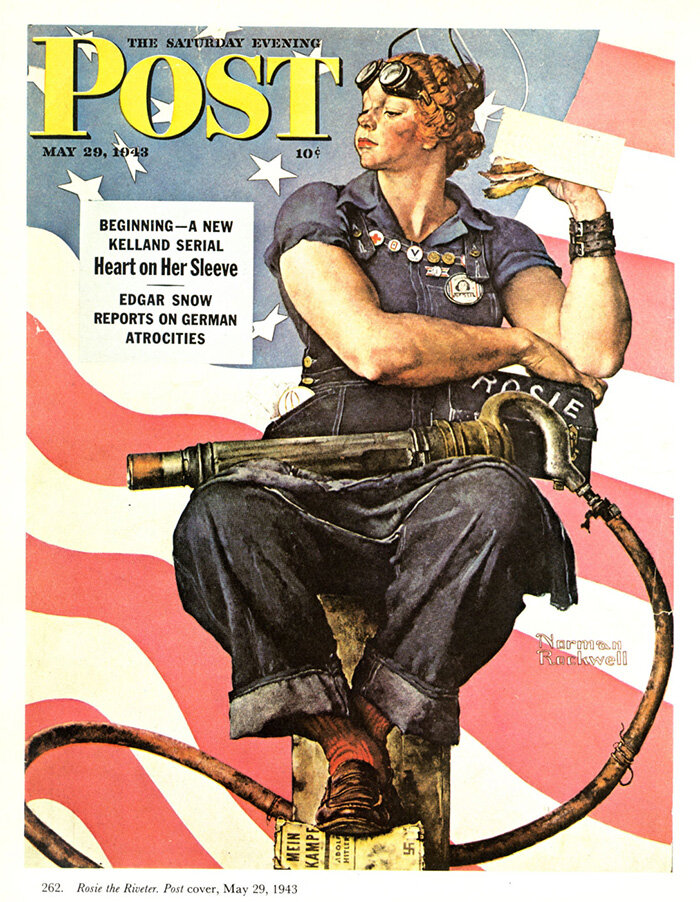

This image of a young woman rolling up the sleeve of her coverall and making a determined fist was produced for the Westinghouse Electric Company and did not become associated with the name “Rosie” until decades later.

Many of us are familiar with the idea that women have been involved in American war efforts since the early 20th century-- J. Howard Miller solidified the image of Rosie the Riveter in the American collective memory in 1942 with his famous illustration. The image of a young, white woman with impeccable makeup, the sleeve of her coveralls rolled up and hair covered with a red bandana, with the text ‘We Can Do It!” declared in bold font at the bottom conjures up a sense of patriotic duty. It’s believed to originally have been part of Westinghouse Electric Corporation’s wartime production campaign to recruit female workers. [1] In fact, the name ‘Rosie’ did not become associated with the image until Norman Rockwell’s 1943 version of the illustration appeared on the cover of The Saturday Evening Post, and it was likely that female industrial workers never even saw the image until it resurfaced decades later in an advertising campaign. [2] Still-- when we think of women in wartime, most of us think of Rosie.

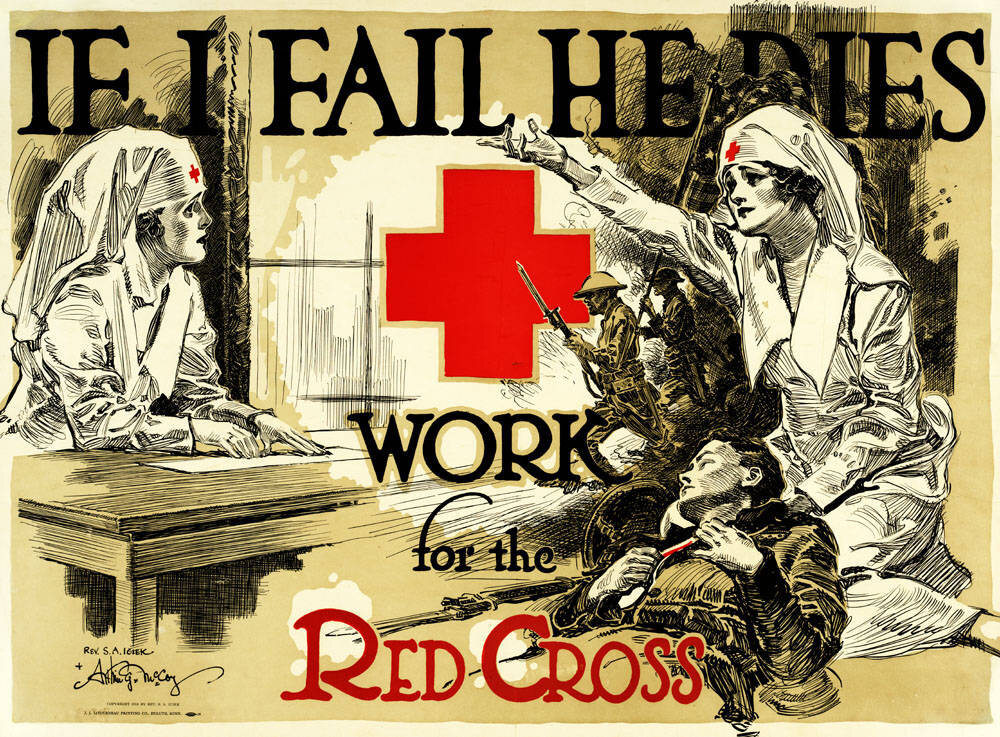

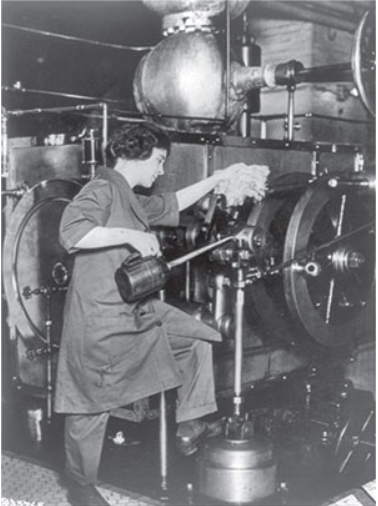

But who were the real Rosies of our factories and production lines? And even earlier, the thousands of American Red Cross nurses who served the nation in World War I? NBIM’s digital archives provide us with a look back at these women doing crucial jobs to support war efforts throughout the first half of the 20th century.

World War I

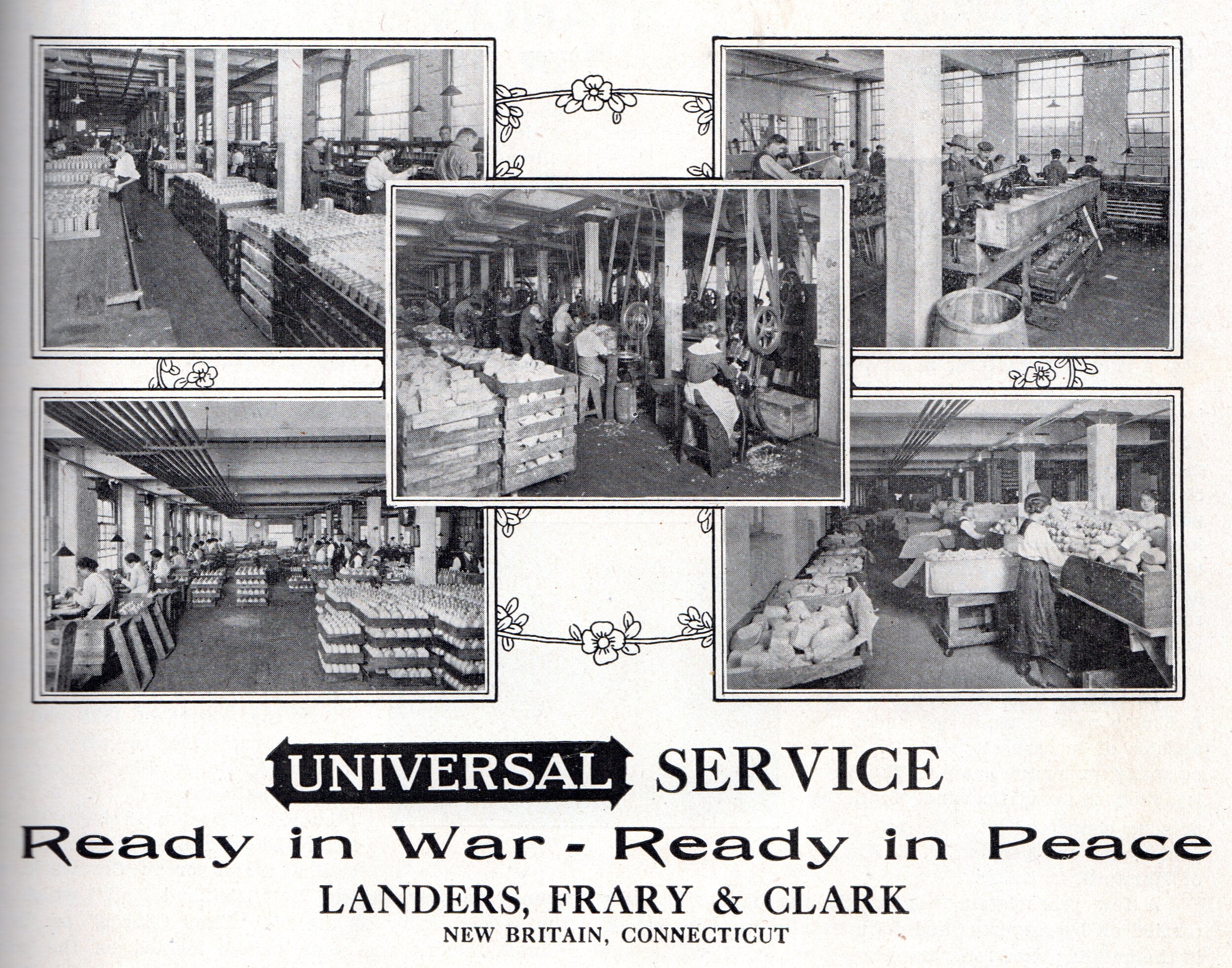

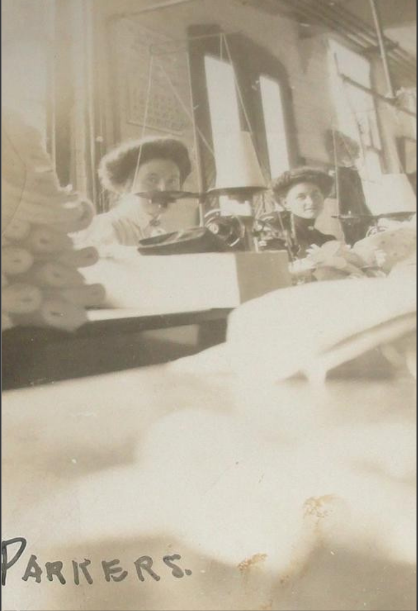

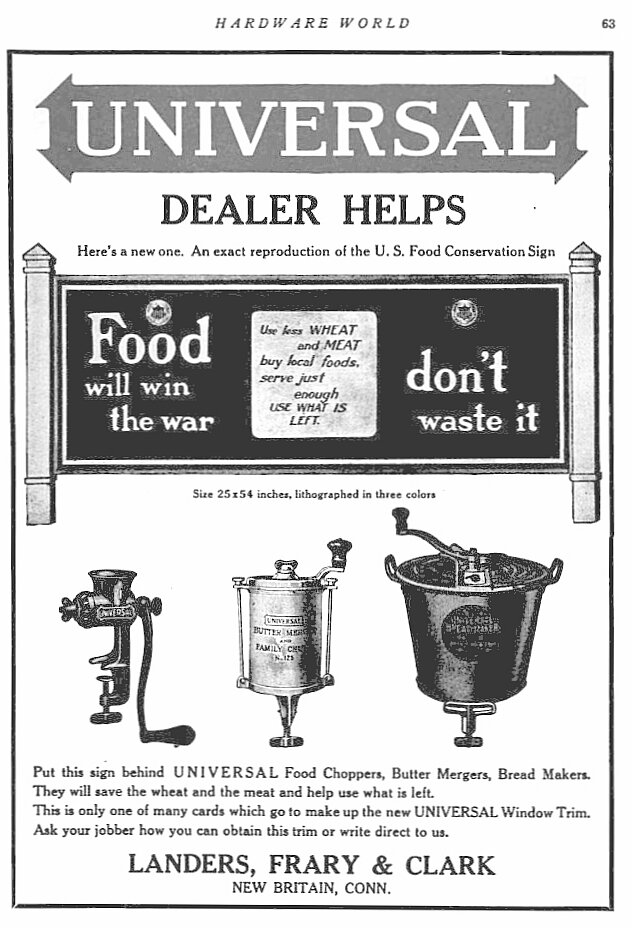

In the industrial sector, early 20th century women found employment in factories and sweatshops. They operated sewing machines, sorted feathers, rolled tobacco, and other similar tasks. [3, 4] World War I saw a huge increase in demand for "pink-collar jobs." The military needed additional personnel to type letters, answer phones, and perform other secretarial tasks. Eleven thousand women worked for the U.S. Navy as stenographers, clerks, and telephone operators. [5] The Parker Shirt Company of New Britain employed dozens of women as seamstresses, and in the summer of 1917 fulfilled an order for 36,000 uniform shirts for the United States government.

In addition to factory work, nursing was also a defining aspect of women’s work. Red Cross nurses began providing military aid as early as 1898 during the Spanish-American War, and was formalized as the Red Cross Nursing Service in 1900 by federal charter. [6] This established a nursing reserve for aid and preparedness in times of war, and eventually led to the creation of the U.S. Army Nurse Corps, still in its infancy at the outbreak of World War 1 in 1914. These Red Cross nurses and Red Cross Reserve nurses played a crucial role in the war, both on the front lines and home front.

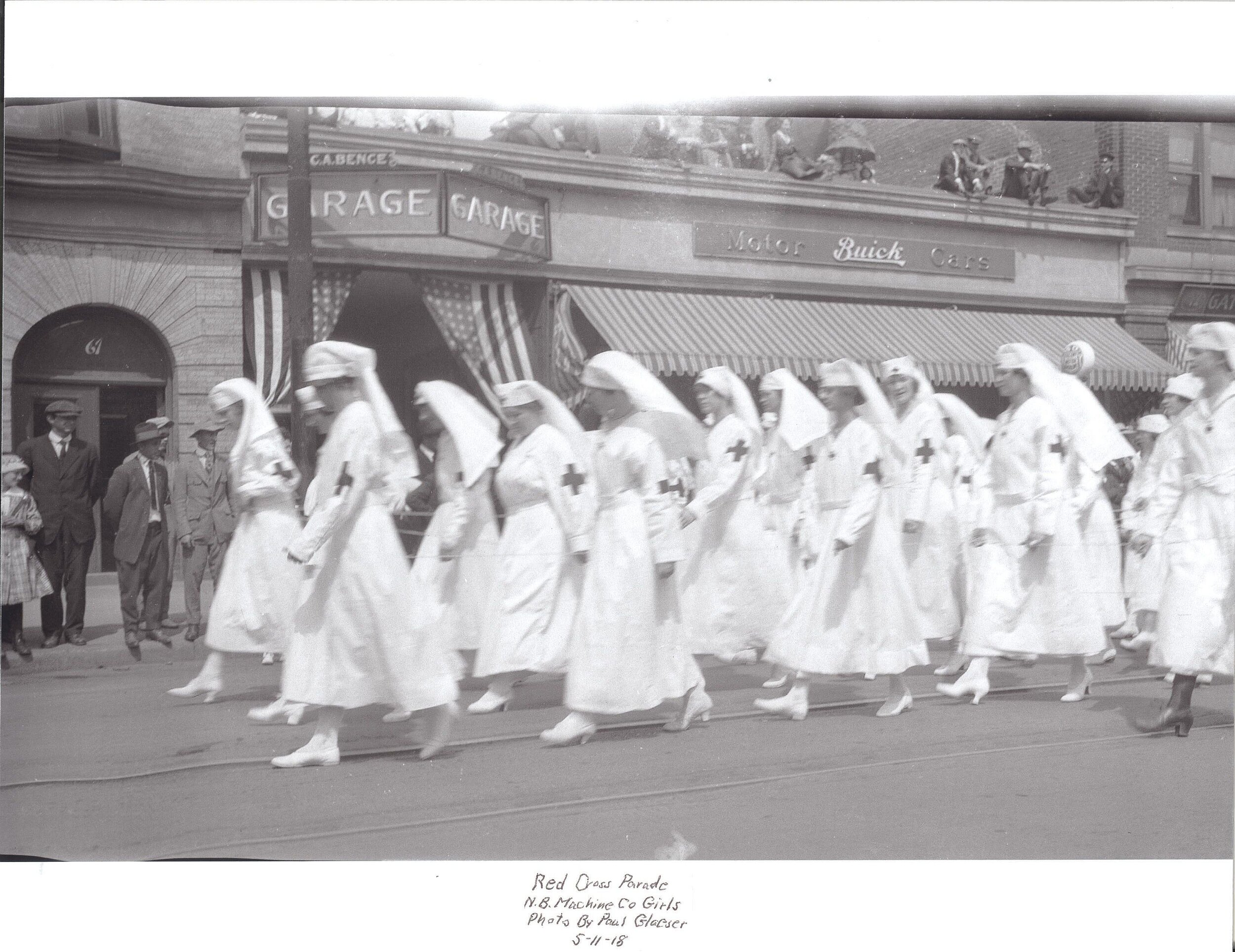

In New Britain, that took the form of Red Cross parades, which snaked their way through the city and raised funds and recruited volunteers to war time services. Civilian nurses and factory workers all participated, as stated in this excerpt from a 1918 Hartford Courant article.

“Preparations are now nearly complete for the big Red Cross drive from May 20 to 27, when New Britain must raise $100,000 of the 100,000,000 fund Uncle Sam needs for his loyal sons. New Britain’s quota of these sons has been among the first to enter the trenches and they have already covered themselves with glory, so that the people back home have every reason for giving the second war fund drive their most enthusiastic support…. The factories will close for the afternoon, and they will be represented by thirty or more floats in the parade…. Every patriotic woman in New Britain is invited and expected to march… the representatives of the school are to be girls only. [The girls] are to be dressed in white and wear the Red Cross in some form.” [7]

Hundreds of New Britain women turned out in nursing uniform for these parades, many of them bearing signs and banners with slogans and the names of companies committed to the war effort. Large floats showcased their wartime production and stirred up patriotism for the cause. As one large float proclaimed, “Over there, over here!”

Additionally, Red Cross workers were responsible for manufacturing war goods. In New Britain factories, Red Cross workers made clothing for hospitals and refugees. Elsewhere women helped produce munitions, gas masks, and other front-line essentials.

World War II

By the time the Second World War broke out, even more women had joined the workforce as secretaries, teachers, nurses, and other traditionally “pink-collar” professions. Western women became increasingly reliant on their own employment to feed, clothe, and house themselves and their families, rather than their husbands or other patriarchs. Prior to the war, many of these women were from low-income and minority households. [8] In New Britain, many women were employed as industrial laundresses, seamstresses, and secretaries at companies like Fafnir Bearing, Landers, Frary & Clark, and North & Judd.

This all changed when the United States joined the conflict in 1941. The War Manpower Commission was a federal agency established to increase the manufacture of war materials and was largely responsible for recruiting women to fill industrial jobs in order to balance the agricultural, manufacturing, and other needs of the nation on the warfront and the home front. [9] With this, thousands of American women were able to fill jobs left open by soldiers fighting in the European and Pacific theaters.

By the end of World War I, twenty-four percent of workers in aviation plants were women. At the beginning of World War II, this number had increased dramatically. [10] Mary Anderson, director of the Women’s Bureau, reported in January 1942 that about 2,800,000 women “are now engaged in war work, and that their numbers are expected to double by the end of this year.” [11]

As the workforce shifted, so did the defense industry: New Britain’s factories pivoted from producing household goods and personal hardware to building planes, guns, and producing uniforms and equipment for the military. Landers, Frary & Clark made gun mounts, and mess kits; North & Judd began production of uniform buckles, clasps, and other fasteners under their “Anchor Brand” name. The American Hardware Corporation, Stanley, New Britain Machine Co., and Fafnir Bearing Co. all shifted operations to support the war, and in the process brought hundreds of New Britain women onto their factory floors. These jobs were critical and sometimes dangerous, but without them the defense industry would have floundered-- and women are the reason it did not.

At the end of the war, many women either returned voluntarily to homemaking or were otherwise laid off from their positions when men returned to fill them once more. However, women remained a permanent fixture in industrial jobs and their contributions during wartime led to the increased acceptance of working women through the latter half of the 20th century.

References:

“Rosie the Riveter.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

Sharp, Gwen; Wade, Lisa (January 4, 2011). "Sociological Images: Secrets of a feminist icon" . Contexts. 10 (2): p. 82–83.

Gourley, Catherine (2008). Gibson Girls and Suffragists: Perceptions of Women from 1900 to 1918, p. 103

"Sweatshops 1880-1940". National Museum of American History. 21 August 2017.

Gourley 2008, p. 119

“Red Cross Nursing.” About Us: American Red Cross, www.redcross.org/about-us/who-we-are/history/nursing.html.

“New Britain to Raise $100,000 for Red Cross” The Hartford Courant, Pg. 20. May 12, 1918

“Women in the Work Force during World War II.” National Archives and Records Administration, National Archives.

"Franklin D. Roosevelt: Executive Order 9139 Establishing the War Manpower Commission". www.presidency.ucsb.edu. Archived from the original.

Adams, Frank S. "Women in Democracy’s Arsenal", New York Times, October 19, 1941.

"About 3,000,000 Women Now in War Work" Science News Letter, January 16, 1943.