NBIM Celebrates Black Innovators: Bridgeport’s Lighting Visionary

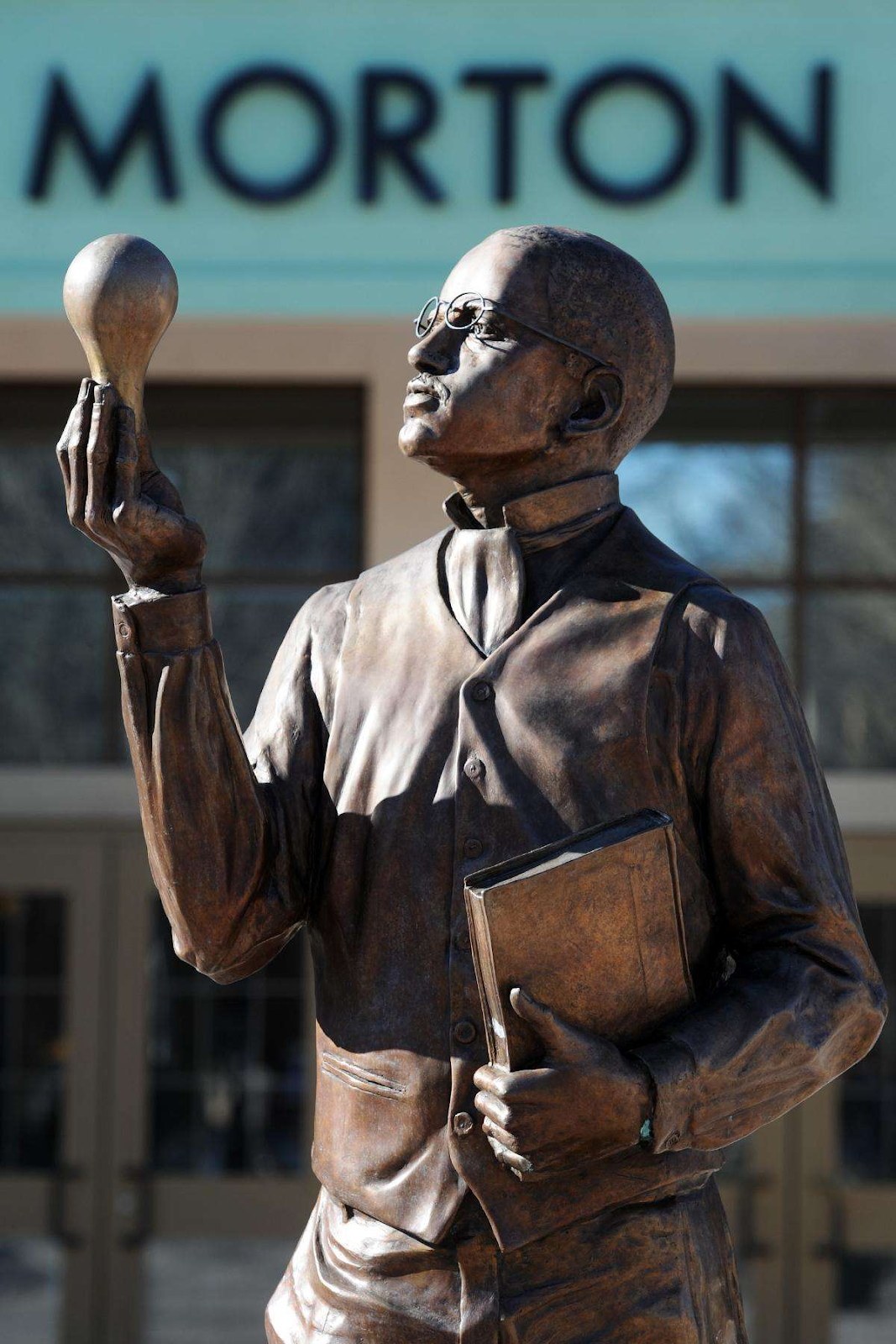

Lewis Howard Latimer, born in Chelsea, Massachusetts in 1848, was the only black member of Thomas Edison’s research team. His work was crucial to the development of the lightbulb, and without it, we would not have modern lighting as we know it today. In his adulthood, Latimer lived in a section of Bridgeport’s South End known then as “Little Liberia” a neighborhood established in the early 19th century by free blacks.

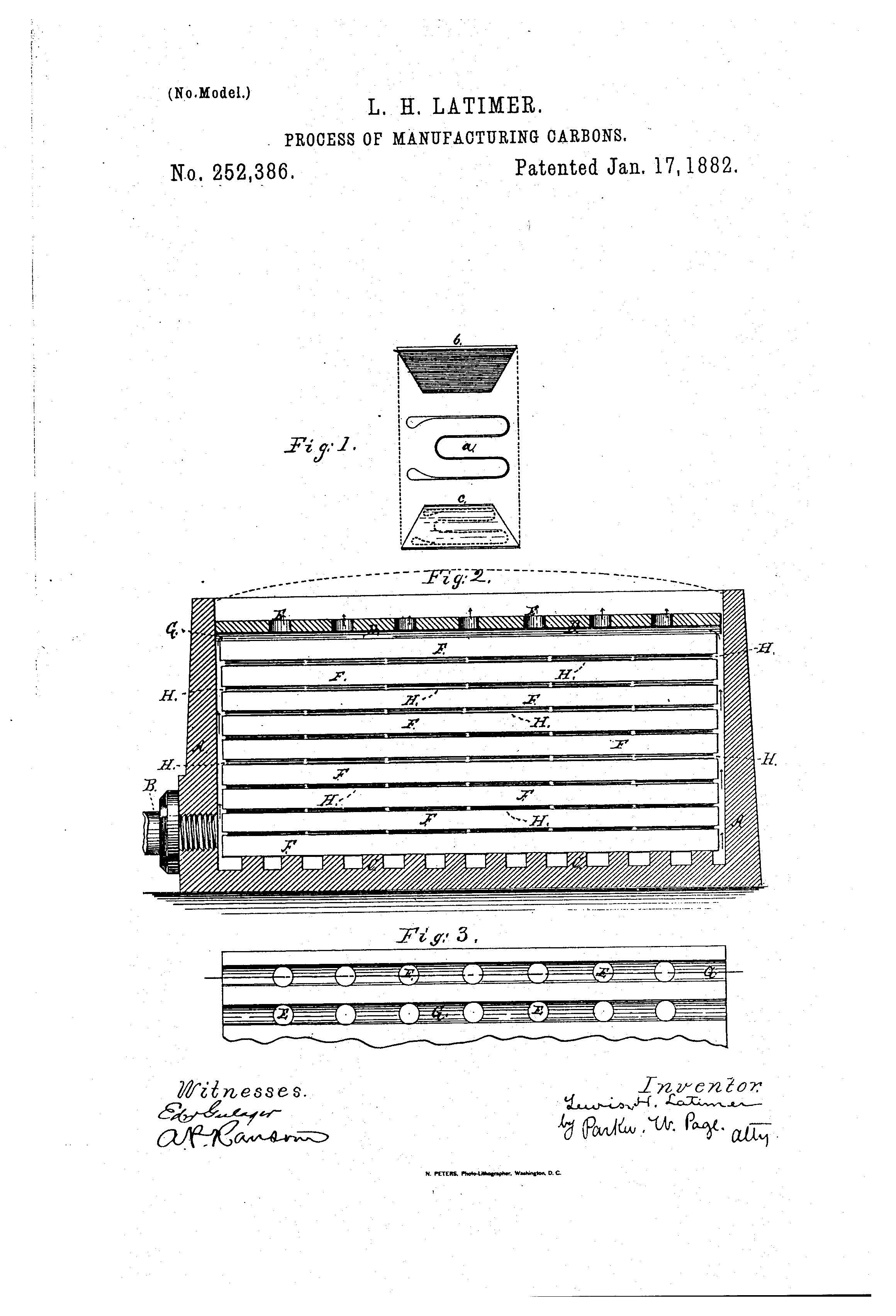

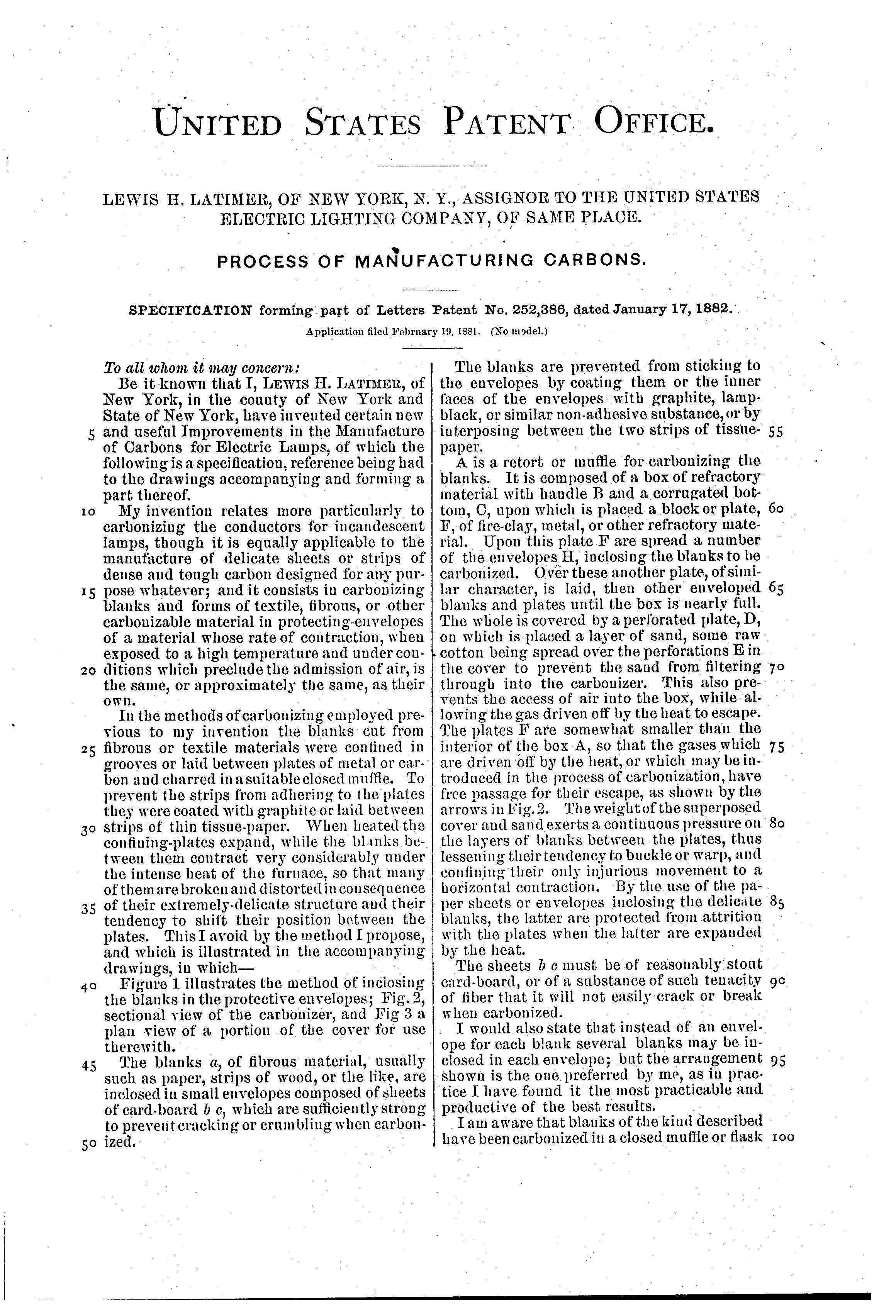

Latimer can claim several patents to his name, including an improved toilet system for railroad cars (U.S. Patent 147,363), the electric lamp (U.S. Patent 247,097), a supporter for the electric lamp (U.S. Patent 255,212), an early air conditioning unit (U.S. Patent 334,078), a locking coat rack (U.S. Patent 557,076), and a lamp fixture (U.S. Patent 968,787). The patent he is most well-known for, however, is U.S. Patent 252,386, his improved process for manufacturing carbon filaments, enabling the production of a lightbulb with twice the lifespan of its precursor.

Latimer enlisted in the U.S. Navy at just fifteen years old, where he served as a Landsman on the USS Massasoit. After the end of the Civil War, he received an honorable discharge and went on to work for a patent law firm as an office boy, where he learned drafting. By the end of his tenure there, he had been promoted to head draftsman. [Fouché, Rayvon, Black Inventors in the Age of Segregation: Granville T. Woods, Lewis H. Latimer, and Shelby J. Davidson]

In 1876, Latimer was employed by Alexander Graham Bell to draft his patents for the telephone, and then only three years later moved to Bridgeport, Connecticut to work for the U.S. Electric Lighting Company, a fierce competitor with Thomas Edison. [Clarke, John Henrik (1983). Ivan Van Sertima (ed.). Blacks in Science: Ancient and Modern.] There, he invented a modification to the process for making carbon filaments which aimed to reduce breakages during the carbonization process. This modification consisted of placing filament blanks inside a cardboard envelope during carbonization.

In 1884, he was invited to work for Thomas Edison’s research team. He was responsible not only for research and development, but translating their research data into German and French. [Center, Smithsonian Lemelson (1999-02-01). "Innovative Lives: Lewis Latimer (1848-1928): Renaissance Man". Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation.]

Latimer was later inducted into the Edison Pioneers, an organization composed of former employees of Thomas Edison who had worked with the inventor in his early years. Latimer was the first person of color to join this group of 100. He is also an inductee of the National Inventors Hall of Fame for his work on electric filament manufacturing techniques.

According to the Landmarks Preservation Commission, he was also an accomplished writer. His publications include a book of poetry called Poems of Love and Life, a technical book, Incandescent Electric Lighting, publications in African-American journals, and a petition to Mayor Seth Low to restore a member to the Brooklyn School Board. He played the violin and flute, painted portraits and wrote plays, and was an early advocate of civil rights. In 1895 Lewis wrote a statement in connection with the National Conference of Colored Men about equality, security, and opportunity. ["Lewis H. Latimer House". Landmarks Preservation Commission. 1995.]

Lewis Latimer died December 11, 1928, in Flushing, NY, aged 80.

You can read the full text of his carbon filament patent here.